The tipping point for software engineering: How AI agents are changing the game

The era of handwritten code is ending. Engineers are becoming orchestrators, and AI agents are becoming the builders.

I've just returned from a relaxing four-week holiday break with my family, and during that period, I was grateful to have some free time to dive into some AI experimentation. What I found-and what many on X.com and across industry are also noticing-confirms that we are truly on the edge of a new era in software engineering.

The Shift: From SWEs to Agent Managers

We are seeing a real shift in the role of engineers. Senior figures like Linus Torvalds and Ryan Dahl (creator of Node.js) have publicly remarked on AI's growing role in software creation-pushing engineers toward higher-level design, review and orchestration. Instead of just writing code, they're orchestrating teams of AI agents that execute the work.

For many engineers—particularly those working on common patterns and established codebases—the nature of the work is fundamentally changing.

Enterprise Trends: Early Days but Rapid Changes

In Australia, forward-looking enterprises—especially ASX 100 companies—are already experimenting with AI. Tools like ChatGPT and Claude are becoming common for knowledge work across business and technology functions, and engineering is just the first field where we're seeing real transformation.

Why is this happening now?

The latest releases of frontier models (Opus 4.5, ChatGPT/Codex 5.2, Gemini 3 Pro) were extremely capable for coding, and were also better able to leverage the agentic harnesses they now come with—such as Claude Code and Codex CLI. While Cursor is a fantastic IDE, I'll exclude that for now, as I have found the models recently have tended to work better in their native harnesses.

These harnesses enable the models to more reliably take action, whether locally or in the cloud, and are developing ever-increasing capabilities in tool calling and long horizon work.

Over the holiday break, I was able to complete six projects that would normally require two to three engineers each and take weeks to build—a rough estimate of 500+ person-hours of traditional development compressed into 4 weeks of me working 1-2 hours a day, and asking the agents to work for 4-6 hours.

The potential for enterprise software (particularly on common patterns and code bases) is immense.

Deep Dive: The Stateless Iteration Loop and Building with AI

What's also clear is that we are very early in the innovation cycle, and new patterns and experiments in agentic engineering are starting to emerge.

One fascinating pattern is the "stateless iteration loop" - dubbed the "Ralph Wiggum loop" by its creator, Geoff Huntley from Australia. The idea is simple but profound: you give an AI agent a detailed spec, let it run tasks in a loop, and it "resets" each time with a clean slate (a fresh context window), picking up where the last iteration left off. This allows the AI to work around context window limitations and continue working autonomously for very long periods.

The power of this model is that, to some degree, with the right definition of done, for example- by providing the specs for a given SaaS system, the agent can work autonomously at length to build/clone said solution. SaaS providers who have relied on complex software as a competitive moat may need to start rethinking their value proposition.

This year, the agent harness will be as important, perhaps even more important, than the model. The harness will connect the agent to capabilities that will enable us to get things done.

Also - there is a clear product overhang, between what the models are capable of, and what the harnesses are enabling them to do. The models are now good enough for most things - we just haven't hooked them in to all the tools/systems that would make them useful to us.

There are other great experiments going on:

- Loom – Geoff Huntley is also experimenting with an agentic system featuring many agents that build software together

- Clawdbot – An agentic system that takes over your machine (virtual or local) to become your personal assistant (a wrapper over Claude Code / Codex CLI, etc.)

- Gastown – A Steve Yegge experiment to delegate software building to teams of agentic systems that grow and evolve to deliver outcomes

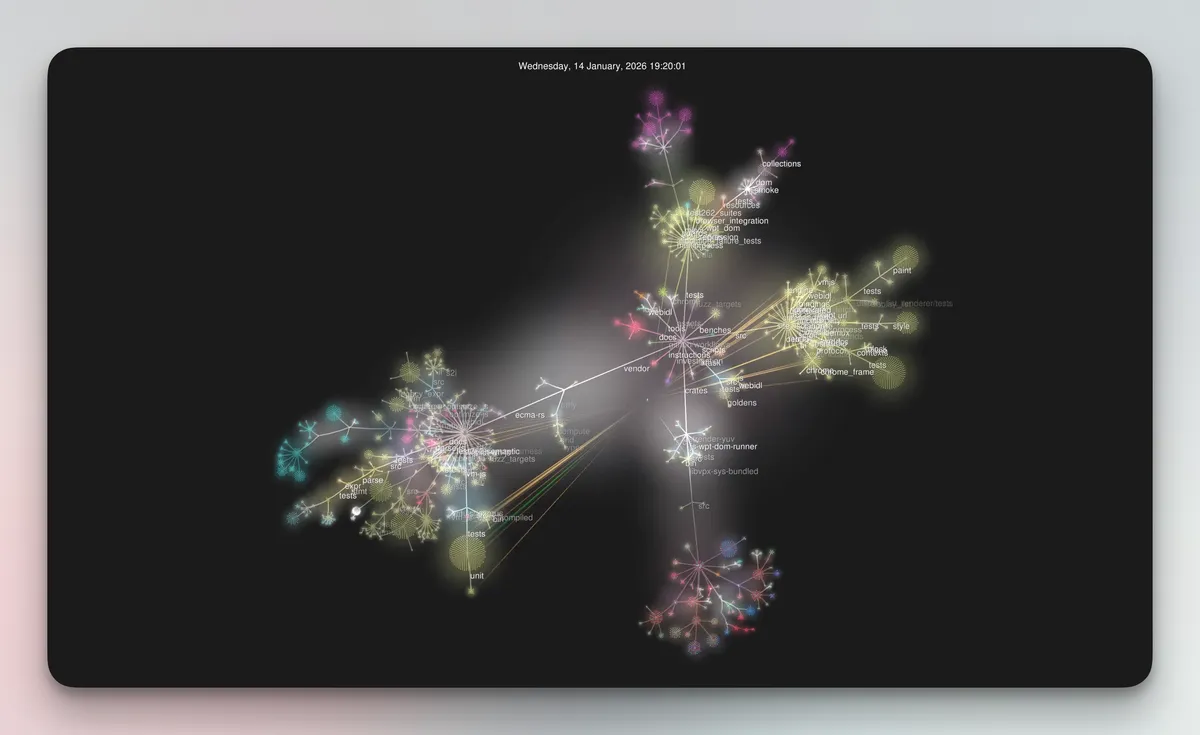

One of my favourite experiments over the break was Cursor's recent project to build a web browser—an incredibly difficult task typically taking tens of thousands of person-hours—where they spun up many agents that operated over the course of a week to deliver a working browser that admittedly "kinda worked." If we had said ten years ago that this was possible, many would have claimed that would be AGI.

Are these experiments and ways of working guaranteed to be a success? It's too early to say - most have their issues, and are in development loops. But they are certainly pioneering new approaches and revealing that engineers will need to think very differently. Engineers will need to think about the business outcome, their architectures, and take the role of Agent Managers, rather than as individuals who hand-roll code.

Personal Projects

Over the break, I was interested to see how far I could push agentic system builds, looking to create software that was reasonably robust and valuable.

As you can surmise from the above- coding agents are very good now. The trick is to spend a sufficient amount of time on good context engineering, including:

- Reference assets

- Agent instructions/ways of working, specifications, and architecture

- Definitions of done, evaluations, and tests

With these assets, the agents can run for many hours building software.

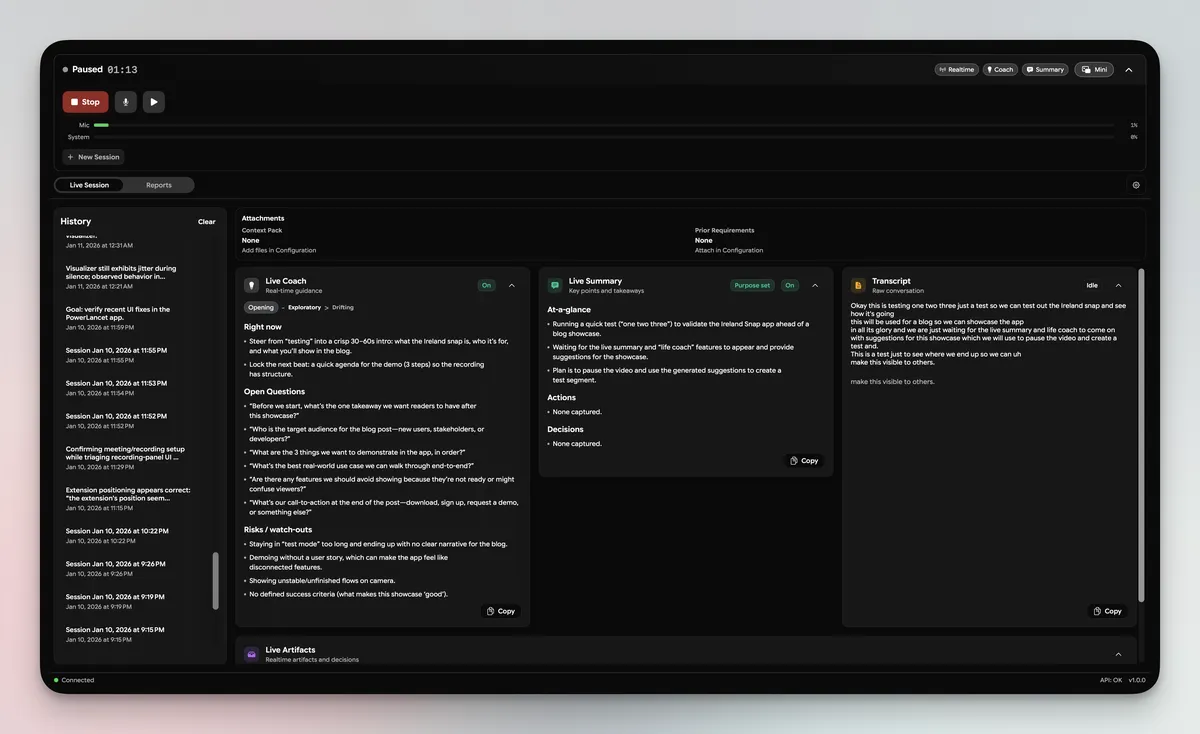

For instance, I created a local SwiftUI app called Parlance. This tool not only transcribes and summarises meetings but also acts as a:

- Live meeting coach – Provides insights and asks probing questions to better manage meetings (whether requirements-gathering sessions, solution design sessions, candidate interviews, etc)

- Requirements gatherer – Builds detailed requirements and solution specifications when prompted live in a meeting, with live editing.

- Report writer – Generates formal documents like requirements or solution design docs on the fly

It effectively turns the rich, tacit knowledge we keep in meeting rooms into formalised, reusable information for downstream AI processing.

Other projects included:

- CPS 230 compliance benchmarking system – Built for banking, this involved sourcing and feeding a large set of regulatory documentation into a new AI system. It now benchmarks over 10 AI models against gold-standard answers across 220 regulatory tests, testing which models best meet Australian banking regulatory requirements across tasks like search and retrieval of data, interpretation of contractual documentation (MSAs, SOWs), and execution of workflows aligned to CPS 230.

- Internal design system – A shareable component library for a new brand we are working on, enabling new users to see the design systems, download / reuse key assets.

- Clawdbot experimentation – Testing a new open-source personal AI agentic system that shows a glimpse of what Apple, OpenAI, Meta, and Google are building towards. A deep-dive blog on this is coming soon.

- Real-time coding coach – A voice/text assistant to support my agentic AI efforts on languages and code bases I'm working with—a little bit like Iron Man's Jarvis, but for agentic engineering.

- Enterprise knowledge work automation – Experimenting with Claude Code / Codex CLI as a way to mass-build knowledge work items for enterprise. This was wildly successful. For example - I was able to build an upskilling course on agentic engineering for my team (with over 50 hours of course material), and will be part of a major upskilling effort for the non-engineers in our consultancy as we progress into 2026.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead for AI and Knowledge Work

Engineering and software development are at a tipping point, where AI handles more of the "doing" and humans strategise, guide, and review.

But the change won't stop there. By the end of this year, we will likely have agents spawning many agents that predominantly work with each other—and not humans—for most of their time. What will the role of a software developer look like then, when we are not just working with one agent, but with scores-or more--of agents who can work for hours on end?

For engineers, I believe the future is bright. While individual companies may need fewer traditional developers, the discipline itself will grow. We'll see more engineers acting like Senior Architects or Heads of Engineering—people whose ability to see the big picture and orchestrate the symphony will be paramount.