How I vibe-coded an LLM Decision Council that beats GPT-5.2-pro for executive work

Nine months ago I tried building an LLM council with ChatGPT‑4.1 and 4o to help me build executive deliverables and make decisions in my role.

I got part of the way there, but the project stalled.

When Andrej Karpathy shared his LLM Council build, it was the nudge to dust off the old designs and see how far I could push some of the new coding specialist models - OpenAI Codex Max and Claude Opus 4.5 - on that original idea. To my surprise - these models built the platform to a working end-state with only light nudging from me.

This post is the story of that build, how it compares to Karpathy’s original LLM Council, and why the result sometimes beats ChatGPT‑5.2‑pro in ChatGPT on the work I actually care about – and what that says about how far AI coding agents have come in 12 months.

*Karpathy - LLM Council Nov' 25

*Karpathy - LLM Council Nov' 25

TL;DR

- I wanted two things from this experiment: (1) test how far I could vibe‑code an LLM council using Cursor plus OpenAI Codex Max + Opus 4.5, and (2) see if a council could match or beat ChatGPT‑5.2‑pro on my day‑to‑day tasks.

- Nine months ago, ChatGPT‑4.1/4o couldn’t get this over the line; today, OpenAI Codex Max and Opus 4.5 managed to build a working council with minimal manual edits in a weekend.

- The platform is a multi‑seat decision council that runs different ChatGPT‑5.2 variants and reasoning levels through a Delphi‑style process (analysis → critique → Chair synthesis) and often produces better-structured, more reliable outputs than a single ChatGPT‑5.2‑pro call across some of my key workloads.

- It’s not perfect – there are real gaps in this version around eval harnesses, enterprise observability, and governance. It’s not built for production scale yet – it runs in my own environment with auth, Docker, security, cost tracking and logs – but it’s now part of my daily workflow and a good testbed for what AI coding agents can do today.

- One big takeaway: prototypes are cheaper than ever. With AI, we can spin up experiments and test ideas with teams and customers much faster and at far lower cost. It's so much easier to just build things now.

Context: Why I Wanted My Own Decision Council

Karpathy’s LLM Council landed at exactly the right moment.

It made a simple point: instead of trusting a single model, you can treat models like a council of experts. You send your prompt to all of them, they answer independently, they review each other’s work, and then a “Chair” model synthesises a final answer.

That caught my eye because it lined up with three things I already cared about:

- Model diversity: I don’t want to bet everything on one vendor or one model family.

- Evaluation in the loop: Real‑world work doesn’t look like synthetic benchmarks; I want per‑prompt evaluation where disagreement is visible.

- Enterprise reality: Our clients sit under different regulated entities and care about vendor risk, model risk, and audit trails.

Over time I’ve started to think of this less as “multi‑agent chat” and more as a decision council: a small group of deliberately different roles (strategy, risk, architecture, decision science) that happen to be implemented with LLMs.

Karpathy’s repo was an interesting pattern. I wanted something more opinionated and closer to my own use cases, but still small enough to build as a ‘weekend project’.

So I set myself two constraints:

- Constraint 1 – Vibe code it: Let OpenAI Codex Max and Opus 4.5 write almost all of the code. My job: articulate intent, review diffs, and course‑correct. I wanted to see how far the models could get on their own. My tools of choice: Cursor, Codex CLI / Cloud.

- Constraint 2 – Council as product: Build something I can actually use in my consulting and product work as an improvement to current processes, not just a toy.

The First Attempt: When ChatGPT‑4.1/4o Ran Out of Steam

I actually tried this nine months earlier.

The spec was almost identical:

- Backend in Python and TypeScript.

- Simple web front‑end with a ChatGPT‑style layout.

- Three‑stage flow: answers → peer review → Chair synthesis.

- Basic config for multiple providers.

ChatGPT‑4.1 and 4o were good enough to scaffold pieces – a FastAPI or Node backend here, a React shell there – but a few things consistently broke the build:

- Cross‑file coherence: The more we iterated, the messier imports, types, and shared state became. Too much time was spent untangling things.

- State management: Any slightly non‑trivial front‑end state led to subtle bugs: race conditions, half‑rendered components, broken streaming - which the models could not handle.

- Refactoring fatigue: Once the code hit a certain size, the models struggled to refactor safely across multiple files.

I could have pushed through manually, but that defeated the point. The whole experiment was about seeing how far the models themselves could go.

So the repo sat idle.

The Rematch: OpenAI Codex Max + Opus 4.5

Fast‑forward nine months. OpenAI Codex Max arrives – highly controllable and precise with good context, but slow. Claude Opus 4.5 lands soon after – faster, strong on reasoning and code, but still prone to overconfidence and the occasional hallucination.

I dusted off the original idea and ran a slightly updated approach:

- Start from a blank repo. Empty project with a clear goal.

- Invest as much time as possible in context engineering. Pull in Karpathy’s repo and a few others, plus specs for the OpenAI and OpenRouter SDKs, FastAPI, key libraries and some sociology and psychology texts on decision making.

- Define the system before coding.

Draft

AGENTS.md,architecture.md,prd_llm_council.mdandbusiness-process-flow.md, all cross‑linked so the models can "walk" the design. - Write a concrete plan.md Break the work into ordered steps from backend skeleton → council pipeline → UI → config → persistence → tests.

- Then let the models drive.

With docs, plan and

.envkeys in place, hand implementation over to OpenAI Codex Max and Opus 4.5.

A note on the business process flow and council design: every run starts with triage (is this question important enough for a council?), moves into parallel analysis from different seats, then a targeted peer‑review round, and finally a synthesis pass.

I’ve structured it this way because research on group decision‑making, Delphi‑style iterative surveys, and social psychology around dissent all point to the same pattern: you get better decisions when you deliberately surface conflicting perspectives, keep them independent for as long as possible, and only then force a reconciliation with a clear rationale.

This time, both the process and the results from the build were markedly different.

- OpenAI Codex Max handled project structure, typing, and dependency wiring and quickly took the project to version 1.0

- With the core engine built, Opus 4.5 was excellent for prompt design, UI design, API edge‑cases, and explaining trade‑offs.

- The two together could fix bugs, introduce new features, and refactor without collapsing the whole codebase. Though, on the whole, I found Codex better for reviewing and managing the codebase.

My human contributions were mostly:

- Designing the council workflow and detailing how each agent should work

- Tightening a handful of prompts.

- Working with the coding agents to resolve bug fixes and issues.

The end result is a working LLM council that, in practical use, sometimes beats ChatGPT‑5.2‑pro on the tasks I actually care about.

Inside the LLM Decision Council

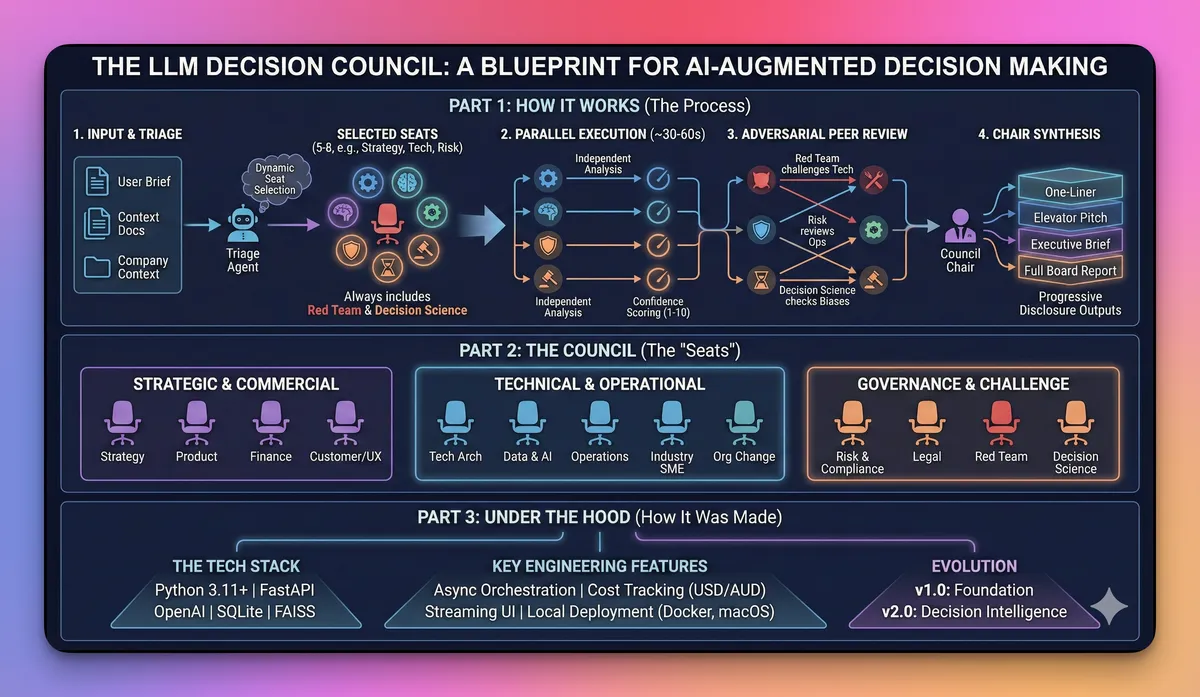

At a high level, my council still shares the same three‑stage shape as Karpathy’s – answers, critique, synthesis – but under the hood the pipeline is closer to a Delphi‑style decision process.

1. How the Decision Council Runs

Behind the scenes, an orchestrator runs a Delphi‑style process:

- Triage and task selection

Check whether the question is council‑worthy and pick the right task preset (

diagnose_problem,design_solution,review_solution,client_ready_brief,pre_mortem, etc.). - Round 1 – Parallel seat analysis A subset of the 13 seats (Strategy, Product, Tech Architecture, Data & AI, Risk/Compliance, Legal, Finance, Operations, Customer/UX, Org Change, Industry SME, Red Team, Decision Science) runs in parallel on the same brief, each with its own persona and structured output template.

- Round 2+ – Informed deliberation (optional) Seats can revise their view with awareness of others, à la Delphi.

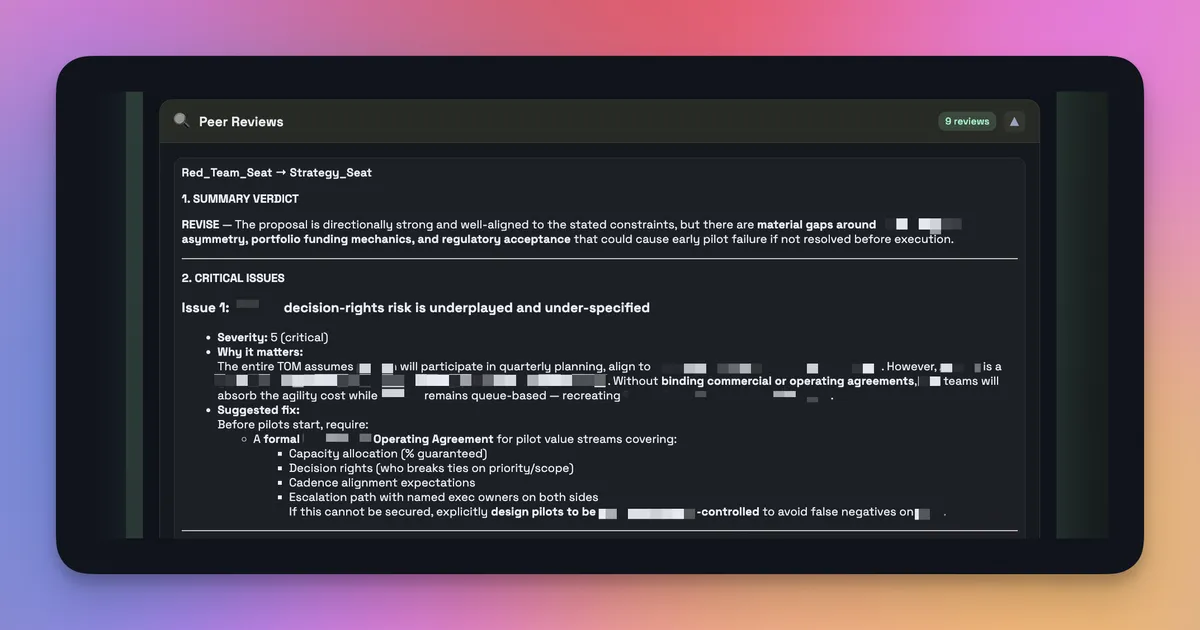

- Pairwise adversarial peer review Certain seats are wired to challenge others (for example, Red Team → Strategy/Tech; Risk/Compliance → Data & AI/Operations; Decision Science → Strategy/Chair).

- Chair synthesis A dedicated Chair seat pulls everything together with progressive disclosure (one‑liner → exec brief → full analysis) and confidence synthesis.

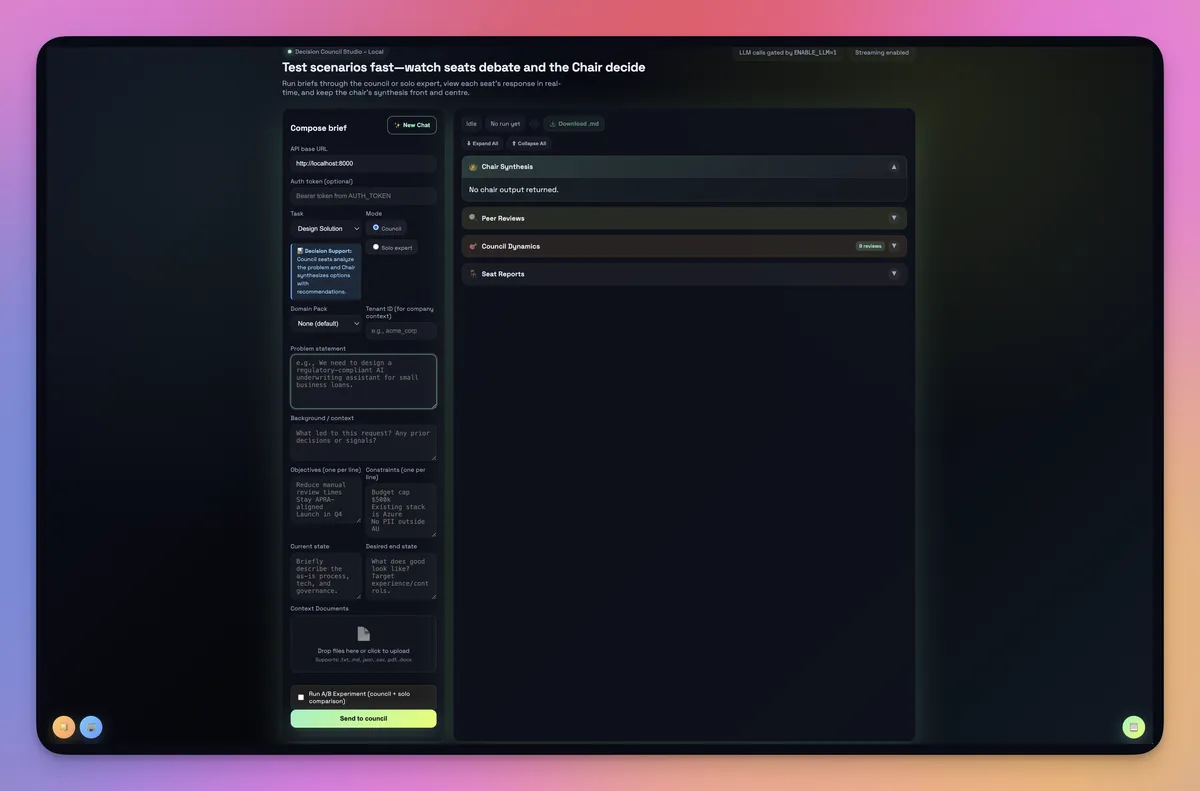

Starting Screen

Starting Screen

Conceptually, this still collapses down to three stages – answers, critique, and synthesis – so it’s easy to explain. In code, it’s an async FastAPI service with a decision orchestration layer on top of OpenAI’s Responses API rather than a single “call all models once” loop.

On top of that, the system adds:

- Config‑driven councils, seats and tasks: seats, models, tasks, and tenants are all defined in config, not hard‑coded.

- Seat and model abstraction: today every seat uses OpenAI models (fast vs reasoning variants tuned per role), but the orchestrator is ready for other providers via adapters.

- Runs, history and costs: each run is stored with its structure, seat outputs, and a cost breakdown (USD/AUD) so I can replay or compare model mixes later.

2. UI Design

I have gone for function over form, choosing to update the UI later for aesthetics. In addition, rather than hide everything behind a single chat box, the UI design attempts to make the process obvious:

- Model responses in parallel: each model’s answer appears in its own panel.

- Critiques visible: for a given prompt, I can inspect how models ranked each other and read their short critiques.

- Chair view: the final answer sits alongside a short “why I chose this” section.

- Phases and costs in real time: the UI streams seat outputs and council phases over SSE, along with a simple USD/AUD cost estimate for the run.

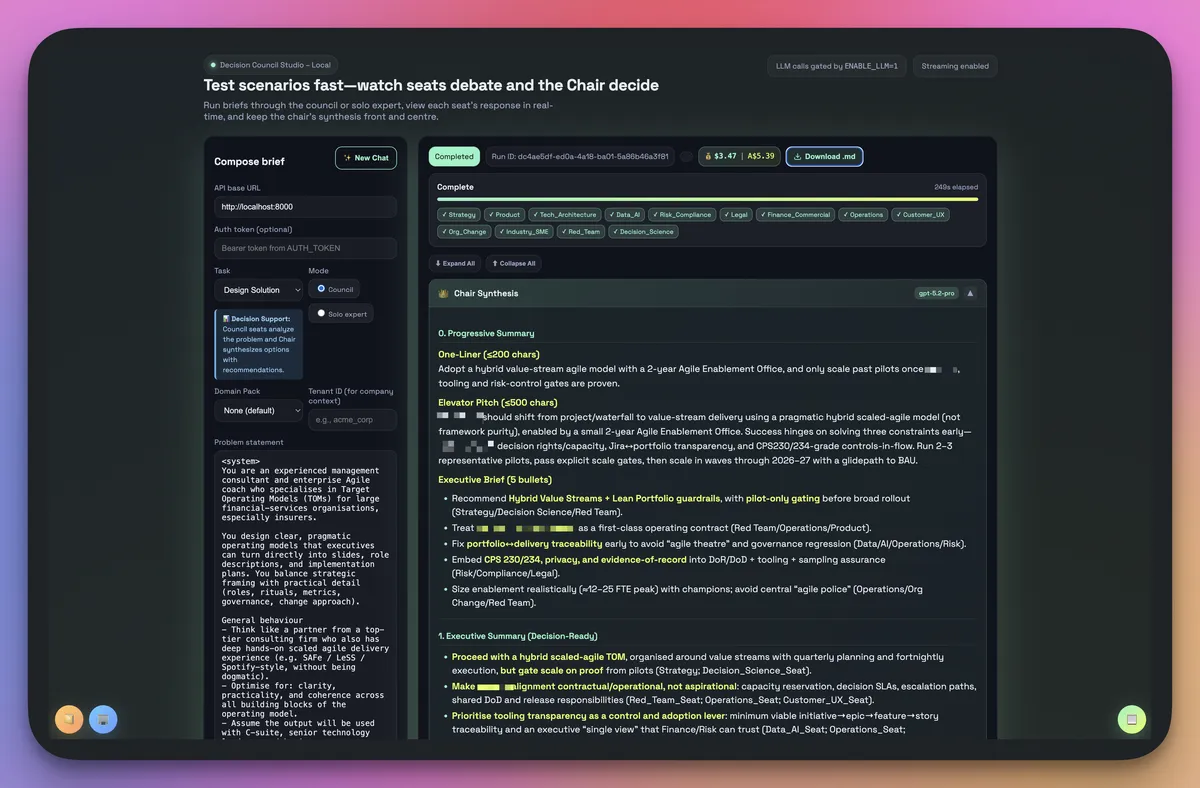

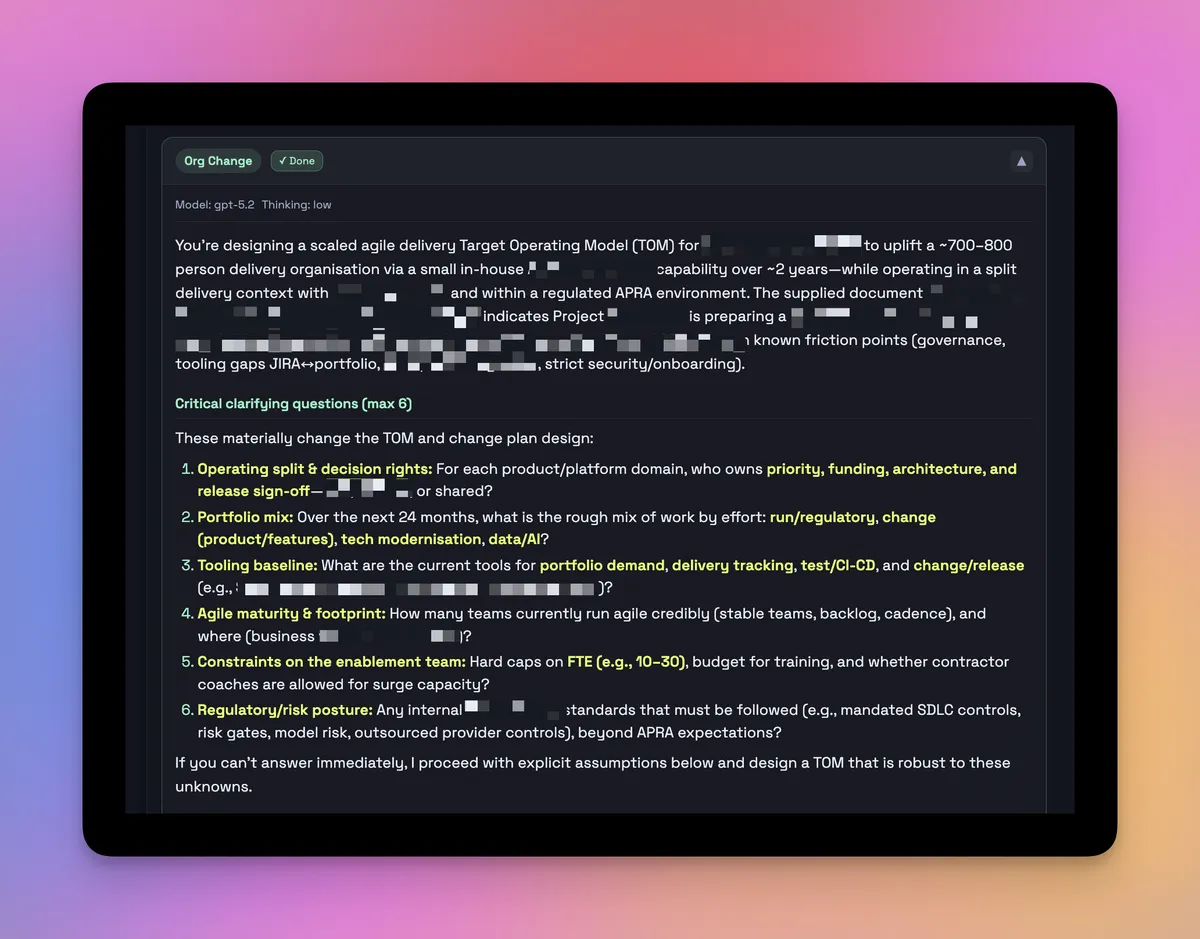

Sample Chair output w/redactions - the full report is much longer and detailed than this screenshot, including tables / charts

Sample Chair output w/redactions - the full report is much longer and detailed than this screenshot, including tables / charts

That matters, because a big part of the value is seeing where the models disagree. I don’t always accept the Chair’s verdict; sometimes the most interesting signal is that one model is stubbornly dissenting. I also lean on the Chair’s progressive disclosure – a one‑liner, a short exec summary, and a full synthesis – so I can skim or paste the right layer straight into a deck or email.

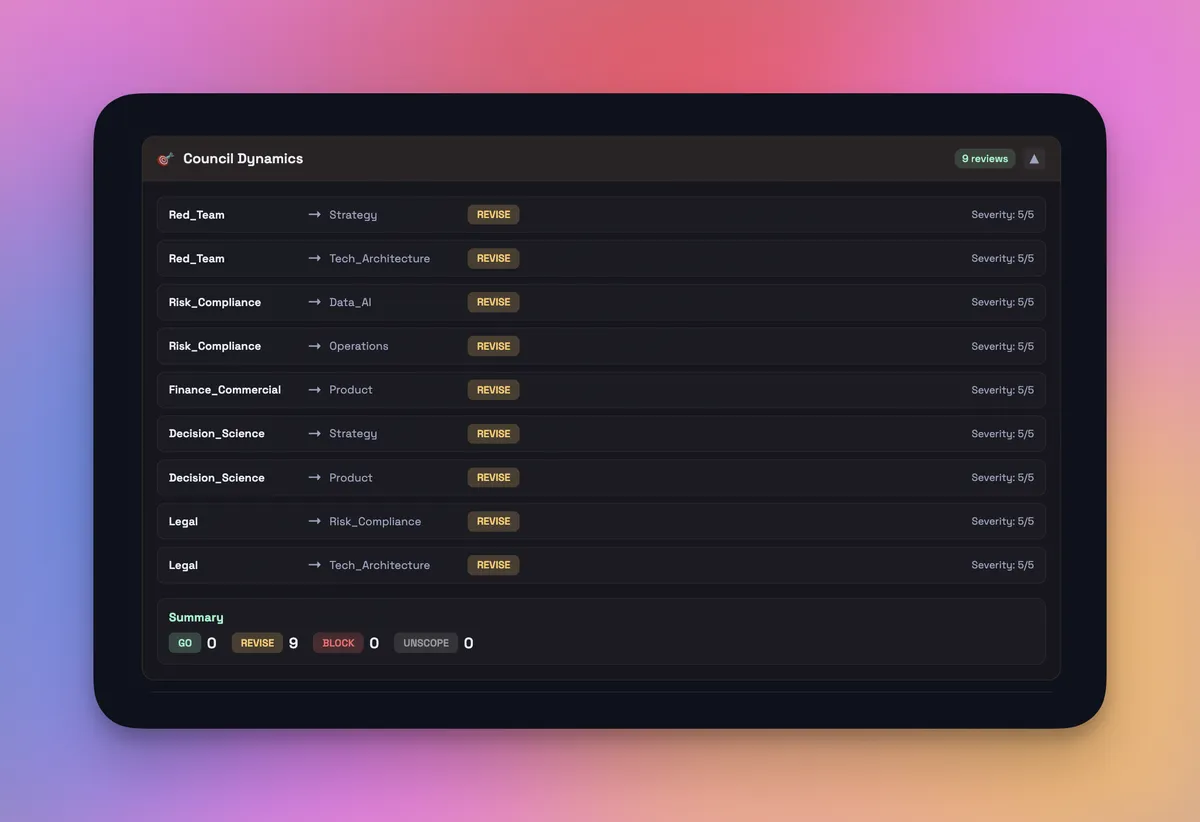

Peer review example w/redactions - seat provides feedback for action

Peer review example w/redactions - seat provides feedback for action

Council Dynamics Summary

Council Dynamics Summary

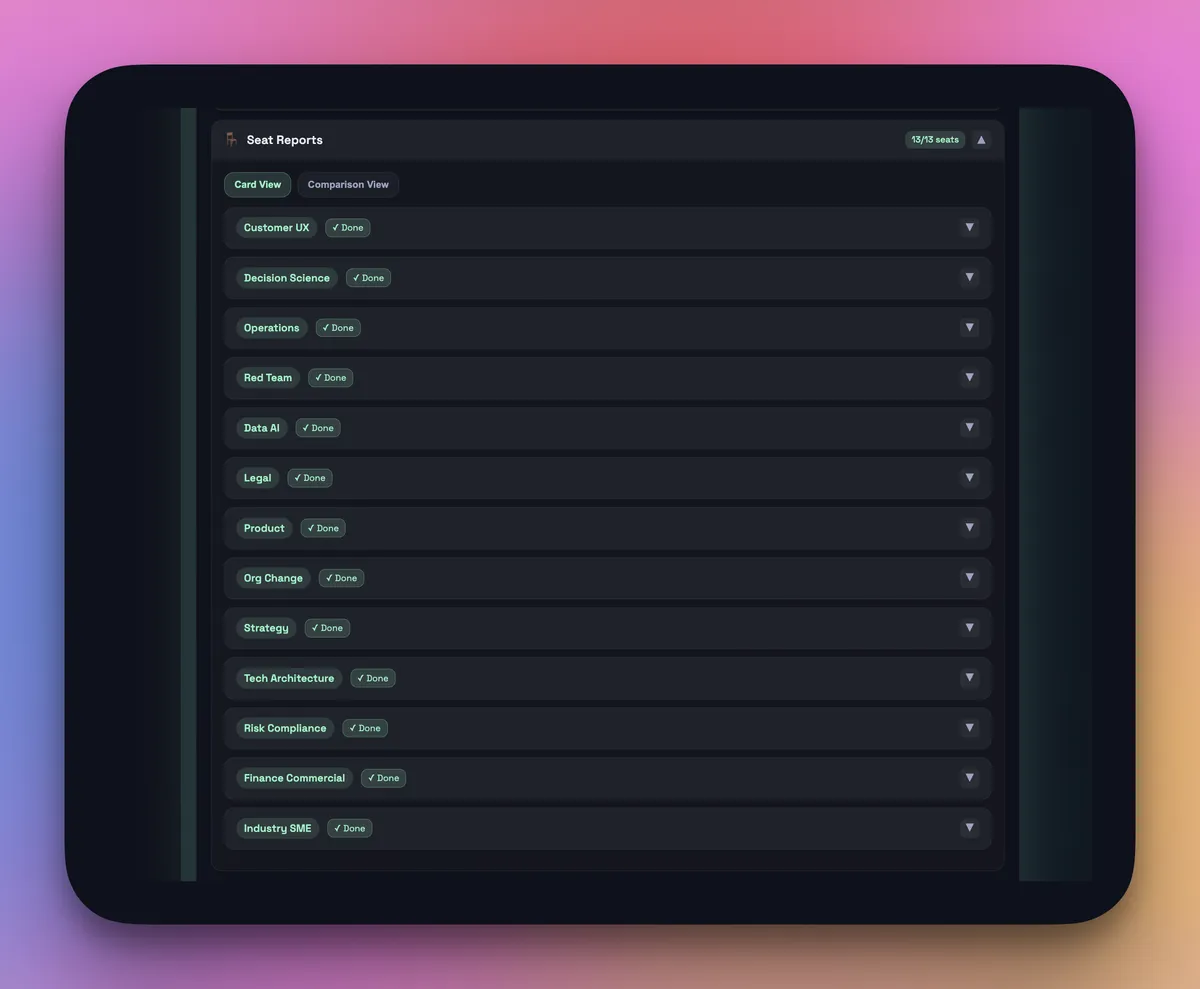

Seat run summary

Seat run summary

3. Tuning for My Workflows

I don’t run every question through a council. That would be expensive and slow. Instead, I’ve tuned it for a few specific workflows:

Architecture and design questions When I’m drafting an AI or systems architecture, I’ll send the same prompt through multiple models and see how they decompose the problem. The council output tends to surface blind spots and alternative patterns.

Risk and control framing For APRA/ASIC‑flavoured work, one of the council seats is always a “sceptical risk officer” prompt profile. It reliably tears into weak assumptions and missing controls.

Code‑adjacent reasoning Not raw codegen – Cursor is still better there – but decisions about approach: how to structure modules, where to put boundaries, how to design interfaces.

Target Operating Model / Organisational Design Complex multi-faceted human organisational design issues – with the right raw context and good design principles / frameworks and even personality profiles - this tool can help create balanced target state team designs.

Sample seat report w/redactions

Sample seat report w/redactions

In each of these, the council is used sparingly, for high‑leverage prompts where disagreement matters. One of the most useful “seats” isn’t domain‑specific at all: a Decision‑Science seat that classifies the decision (one‑way vs two‑way door), calls out obvious biases, and forces a quick pre‑mortem (“it’s two years from now and this failed – what went wrong?”). In practice I run a light council (a handful of seats, single round) for scoping, and only switch to a full council (more seats, multi‑round deliberation and peer review) for genuinely high‑stakes questions, often with real documents and company context loaded through the RAG layer.

When does the council beat ChatGPT‑5.2‑pro?

Short answer: sometimes, on the margins that matter to me.

I haven't set up a formal benchmark (yet), but across a few dozen prompts in my real workflows, there is a pattern:

- Single ChatGPT‑5.2‑pro call: strong baseline; good at coherent, well‑structured answers.

- Council run: more nuanced, often more conservative, and better at surfacing multiple valid options with trade‑offs. Councils need context (sometimes bespoke background and ever-present context relevant to their role, or sometimes specific context for the query in question) to offer their best insights.

The cases where the council clearly "wins" look like this:

Ambiguous, multi‑stakeholder questions E.g. "How should ABC Bank Client structure an AI risk committee considering CPS 230 and CPS 234, and other obligations?" The council is better at surfacing different governance patterns, conflicting constraints, and explicit trade‑offs.

Architecture or Strategy / Operating Model choices with non‑obvious trade‑offs E.g. “How to trade off the stated constraints on time, budget, feature breadth, and architectural patterns to deliver the outcome by X date and to Y benefits case” Different models tend to favour different patterns; the Chair is forced to reconcile them.

Long‑horizon reasoning When I ask "what happens in three years if we choose X vs Y?", the diversity of council answers seems to reduce the risk of a single‑model “hallucinated future”.

On simple factual questions, ChatGPT‑5.2‑pro alone is perfectly fine (and cheaper). The council helps when the shape of the disagreement is itself useful signal. Because every seat and the Chair emit 1–10 confidence scores – plus a short note on what would change their mind – I also end up with a crude confidence range and the limiting factors behind each recommendation, which is often more valuable than a single confident paragraph.

What’s better than Karpathy’s original (for my use case)

Karpathy’s LLM Council is intentionally a weekend vibe‑code. For my use, I needed a bit more structure.

Four things appear to be clear upgrades for my world:

Configurable councils and tasks as first‑class objects I can define multiple councils and tasks – "Architecture", "Risk", "Research", "Client Brief" – each with their own seat mix, prompts, and Chair, rather than hard‑coding a single loop.

Persistence, replay and cost awareness Every run is stored with its brief, seat outputs, and a cost breakdown, which makes it easy to replay the same problem with a different model mix and to have a sane conversation about spend.

More opinionated prompts and outputs For example, risk‑focused councils are forced to output options, risks, mitigations, and an explicit recommendation, not just prose.

Role‑based seats and conflict by design Seats are prompted as different stakeholders – strategy, product, tech, risk, finance, decision‑science, red‑team – and some are there specifically to challenge others. Combined with confidence scoring on every seat and the Chair, the goal isn’t polite consensus; it’s structured disagreement the council has to resolve.

None of this is rocket science, but it shifts the council from a "cool demo" to something I actually use with clients and internal work.

What’s still rough

It’s not all upside. A few things are clearly missing if this were ever to be more than a power‑user tool.

1. Evaluation Harness

Right now, there are a few things still missing:

- A small, curated prompt suite of my real tasks (architecture, risk, strategy).

- A simple way to rate outputs (by me or by a separate LLM judge) on clarity, correctness, and usefulness.

- Basic reporting over time as models and prompts evolve.

- A simple harness to compare council runs against a Solo Expert baseline seat on the same prompt set, as described in the PRD.

Without that, this is still anecdotal – useful for me, but not something I’d present as a benchmark.

2. Observability and Cost Controls

I already track tokens, USD/AUD costs, and run traces through the FastAPI layer, which is plenty for a single‑developer setup. A production‑grade council in a bank, though, would need:

- Budget alerts and guardrails on top of those per‑run cost summaries.

- Deeper tracing for timeouts and partial failures wired into existing observability stacks (Datadog, New Relic, SIEM, etc.).

- SLOs and dashboards that risk and architecture teams can actually see.

That’s especially important if this were to be run in a regulated setting.

3. Governance Hooks

Today, the governance story is still light: the system is multi‑tenant‑aware and there’s a decision journal and company context store, but I’m the one reviewing prompts, sanity‑checking outputs, and deciding when to use the council.

If I were deploying this into a large enterprise, I’d want:

- Role‑based access (who can configure councils, who can run them, who can see which logs).

- Clear versioning for prompts and council configs.

- Basic policy enforcement (e.g. certain tasks must use a council; others must not).

- RAG and context management

All solvable – but not yet added to this build.

Australian Perspective: Councils as a Governance Tool

From an Australian lens, LLM councils are interesting for another reason: they map quite neatly to the themes regulators are already pushing.

Vendor concentration risk: Most large Australian organisations are heavily tied to one or two cloud providers and a very small set of model vendors. In this build, every seat still runs on OpenAI, but the council pattern – and the orchestrator behind it – is a practical way to add other providers over time without ripping out the existing stack, and to compare them on real workloads as they arrive.

Model risk and explainability: Under CPS 230/234 and similar guidance, boards are being asked how they govern AI‑driven decisions. A council gives you a tangible artefact: you can literally show the different model opinions, how they were reconciled, and where humans over‑rode them.

Operational resilience: Councils don’t magic away risk, but they make it easier to route around a failing model or provider outage by swapping seats, not re‑architecting everything.

I don’t think “council‑as‑a‑service” is a regulatory silver bullet. But as a pattern, it’s much easier to explain in a boardroom than a generic "AI and human report".

Implications and Take‑Aways

For founders and product teams:

- Use councils for rigorous ideation and peer review: A small council can stress‑test key ideas, artefacts and deliverables by surfacing critical observations and counter‑opinions. That’s especially helpful for solo workers or small teams who don’t always have a real‑world peer group on tap – structured disagreement is one of the simplest ways to reduce decision bias.

- Lean on coding agents to prototype safely: Modern coding tools and agents make it far easier to spin up working prototypes and test hard ideas quickly and cheaply. Treat builds like this council as a safe harbour: a place to try new patterns, learn what breaks, and grow team capability without committing to full‑blown platforms on day one.

- Treat councils as a model test harness: Even if you never ship a council into a product, the pattern is a great way to compare models and pricing. Running the same prompts through different seats, models and configurations lets you see how far cheaper or smaller models can get you on your real tasks, and where (if anywhere) it’s worth paying for frontier‑level tokens.

What’s Next

From here, my priorities are simple:

- Build a tiny eval harness with a dozen of my real prompts and a basic scoring loop, using the Solo Expert baseline seat as the comparison.

- Tighten observability so I can see cost, latency, and failure modes more clearly and hook into the rest of our monitoring stack.

- Use the decision journal more deliberately – tracking recommendations and outcomes for a handful of client and internal decisions – so future councils can learn from past ones.

- Write a follow‑up with a formal set of benchmarks and cross model comparison.

If you’re a business or technical leader playing around with LLM councils like this and want to compare notes, reach out – I’m curious what councils look like in your world.